Flexible retirement eroding the cliff-edge between work and retirement?

In its latest pension reform, Finland relaxed the rules for retirement, giving people more freedom to combine work and retirement. By introducing a new partial pension, Finland is following the old-age pension scheme design of Sweden and Norway. So far, the experiences from all three countries indicate that people want to combine work and retirement income. It remains to be seen whether gradual retirement will become as popular in Finland as it is in Norway, or whether it will stay at a more moderate level, as in Sweden.

The purpose of the partial old-age pension is to encourage people to work longer. According to a recent Eurofound study, Sweden, Norway and Finland are among the forerunners and a step ahead of many other European countries in this respect. The current trend in pension system design seems to be to increase individual choices and options for pension take-up as the retirement ages rise. The pattern in the Nordic countries can be expected to be repeated in, for example, Estonia and Switzerland.

The flexible rules that allow people to draw a partial or a full old-age pension, regardless of the number of hours they work, means that the traditional behaviour of retirement as a cliff-edge at which work stops and retirement begins is eroding.

Adjusted model for flexible retirement

Sweden established its current partial old-age pension scheme two decades ago, followed by Norway in 2011 and Finland in 2017. The current schemes have many similarities in their design, but a look back reveals that Norwegians have taken a big leap as they did not have a statutory early retirement scheme before the reform. What they had was the AFP, a special early retirement scheme, set by collective agreements. It provided generous options for public sector employees and half of the private sector employees between the ages of 62 and 66 years.

One of the major differences in comparison to earlier part-time pension schemes that existed in Sweden and Finland is that the requirement of reduced working hours has been abolished. Work and pension can be freely combined. In addition, incentives for postponing retirement have been increased and the part of the pension that is taken early is permanently reduced. In other words, the scheme is not as generous but it is actuarially neutral.

Keep working while drawing a pension

People drawing a partial old-age pension in Finland take out either 25% or 50% of the pension they have accrued. In Sweden and Norway, the system is even more flexible, with more alternatives.

In Sweden, people can claim annuity after reaching the age of 61, the current limit also in Finland. However, the age limit in Finland will be linked to the rising retirement age. People can take out the partial early old-age pension no more than three years before they reach their retirement age. In Norway, people can take out the pension early, from the age of 62, but only if they have accrued a pension amount that is equal to the full national pension.

Early retirement increasingly popular in Norway and Sweden

According to behavioural economics, people tend to take out pension as early as possible. Indeed, both in Sweden and Norway, early retirement has increased since the partial old-age pension was introduced in these countries. Nevertheless, the majority of Swedes retire at age 65 and the majority of Norwegians at age 67.

People prefer to draw a full pension rather than a partial pension. In both Norway and Sweden, around 90% of those who have taken the early old-age pension are drawing their accrued pension in full.

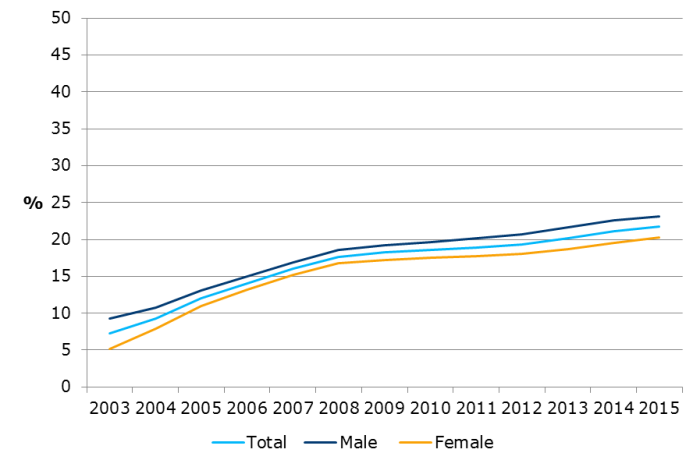

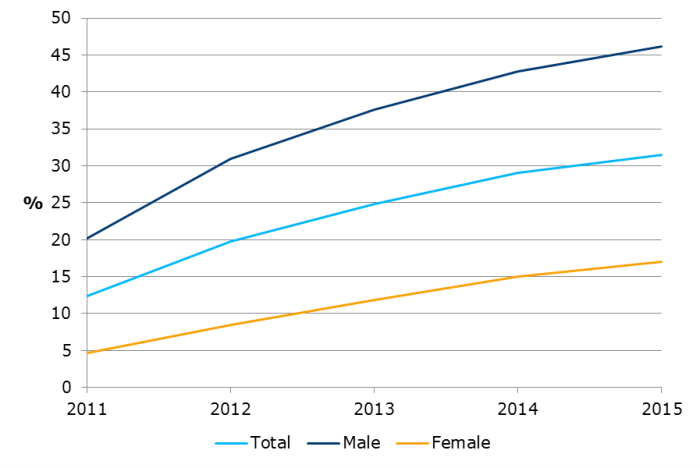

According to statistics published by NAV and Pensionsmyndigheten, every third Norwegian in the age group 62-66 years has claimed an old-age pension whereas every fifth Swede aged between 61 and 64 years has taken their pension early (Figures 1 and 2).

Men behaving badly?

Studies suggest that the possibility to retire flexibly has changed men’s retirement behaviour. This is most eye-catching in Norway, where almost 40% of the men claim their pension as soon as they can, at age 62. The retirement behaviour is clearly two-folded, though, since another 40% wait until they turn 67. However, there is clear a contrast to women: 70% of them take their pension at the age of 67.

The overall picture of retirement is not that clear cut. Most women work in the public sector where it still pays off to take the AFP rather than the actuarially adjusted statutory old-age pension. When taking into account the AFP and the disability pension, the differences between men and women on an early old-age pension diminish.

Furthermore, despite the increasing numbers of early take-out, statistics provided by NAV show that the majority, around 60%, of pensioners aged between 62 and 66 continue to work. It also appears that they are working almost as much as they did before taking out their early pension. The desire to retire early with extra money is powerful, but it does not mean that people want to stop working as soon as they get the cash.

As for Finland, it is still too early to evaluate what the actual consequences of the reform will be. But the available statistics for the first months reveal that two out of three of the applicants are men. A typical partial old-age pensioner is a 61-year-old man who withdraws half of his pension early. The huge number of applications reveals that the partial pension is more popular than the former part-time pension was at least in its last years. The Finnish Centre for Pensions will continue to study the retirement behaviour in Finland.

Figure 1. Share of old-age pensioners (62-66-year-olds) in relation to same age group in Norway in 2011-2015. Source: NAV

Figure 2. Share of old-age pensioners (61-64-year-olds) in relation to same age group in Sweden in 2011-2015. Source: Pensionsmyndigheten