Finland’s policy-makers should focus on lifting older men’s employment rates

While negotiations to form a new Finnish government are ongoing, various commentators are pleading for the new government to be ambitious in its goals to raise employment levels. Only the question is: whose employment levels and by what measure? Some groups in Finnish society are doing well when compared the same groups in other countries, while others are doing worse.

While the Nordic countries usually stand out in international comparisons by having high employment rates, Finland is often seen as the worst pupil in the Nordic classroom. Especially Finnish older men perform poorly compared to their counterparts in the other Nordic countries.

One thing that is often overlooked is that part-time work is relatively uncommon in Finland compared to many other countries. Therefore, it is possible that even if employment rates are low in Finland, the total amount of hours of work performed in the whole economy is actually close to countries that have higher employment rates but at the same time higher incidence of part-time work. A recent report by the Finnish Ministry of Labour indeed suggested that when looking at the so-called full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rates of the population aged 15–64, Finland is no longer the Nordic laggard.

This blog looks at the FTE employment rates of older workers in Finland in comparison to other Nordic countries as well as Germany and the Netherlands. Results are based on calculations with European Labour Force Survey data. More details can be found in this memo (pdf).

More than in other countries, Finnish older workers have full-time jobs

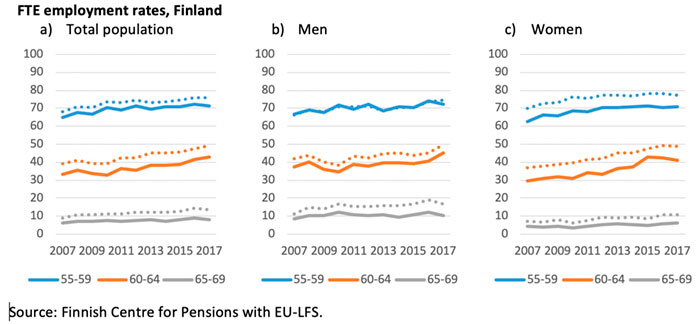

The figure below shows the FTE employment rates (the continuous line) compared to the ‘regular’ employment rate (the dotted line) for age groups 55–59, 60–64 and 65–69, separated by the total population (panel a), men (panel b) and women (panel c).

There is a relatively small gap between employment rates and FTE employment rates, due to most people working close to full-time hours. The gap is larger among women than among men. Men between ages 55 and 59 have working hours that are close to 40 hours a week on average. The gap widens somewhat among the older age groups. Finland is relatively unique in an international context, as women’s FTE employment rates are similar to or even higher than men’s.

In the other Nordic countries, the gaps between employment rates and FTE employment rates among older workers are generally larger. Detailed graphs can be found in the memo (pdf). Sweden has higher employment rates among all age groups, but is otherwise relatively similar to Finland with FTE employment rates close to the regular employment rates. In Denmark and Norway gaps between regular and FTE employment rates are larger, especially among women.

Germany and the Netherlands are interesting countries for comparing because both have witnessed large increases in employment among older workers in recent decades, but also have more traditional divisions between men and women in the labour market. The gender differences in FTE employment rates are striking. Although among men employment rates have caught up to Nordic levels and men work close to full-time on average (or even more in case of German men), women’s FTE employment rates are lagging due to the particularly high incidence of part-time work.

Finnish older men’s FTE employment rates lag, women’s rates are among Europe’s highest

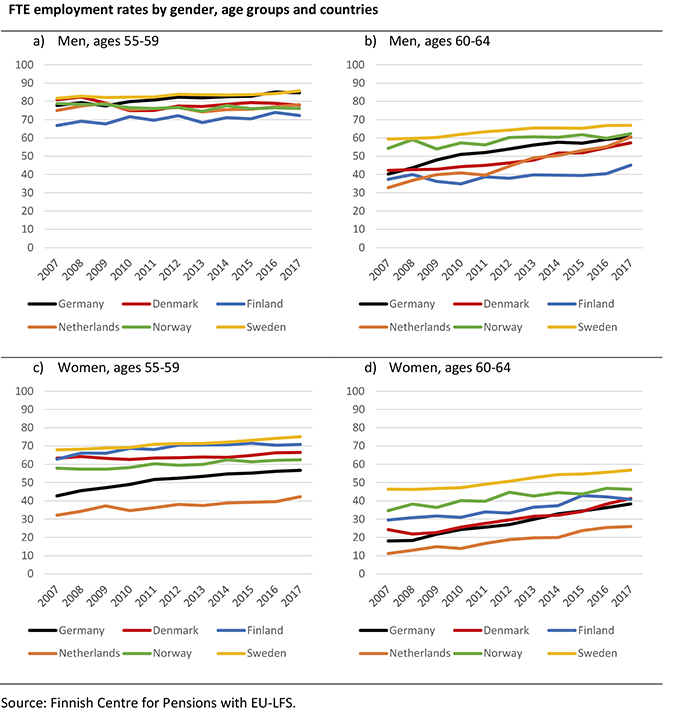

The figure below shows the same FTE employment rates, but now including all countries by gender and age groups to make comparisons easier (the age group 65–69 is excluded because of a small number of cases).

Finnish men clearly have the lowest FTE employment rates in both age groups of all countries. In the age group 55–59 (panel a), FTE employment levels of Finnish men converged with those of men in Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands by 2017, but this was also due to stagnation in the rates in those three other countries.

In the age group 60–64 (panel b), Finnish men were still performing similarly to men in the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark in 2007, but in those countries FTE employment rates rose at a particularly high pace after that, while rates in Finland stagnated.

Compared to men, Finnish women perform much better. Finnish women aged 55–59 had FTE employment rates similar to Sweden (panel c). Danish and Norwegian women had lower FTE employment rates, in particular due to shorter working hours. Germany and especially the Netherlands had the lowest FTE employment rates, not only due to low employment rates, but also because of short working hours. Within the age group 60–64, Finnish women are outperformed by Swedish and Norwegian women, but had higher FTE employment rates than their Danish, German and Dutch counterparts.

Why should we look at FTE employment rates?

Policy-makers aim for high employment rates, arguing that they are needed for the sustainability of public finances and the welfare state. However, personal income taxes and social contributions are based on total income and total income is determined by the amount of hours worked. By taking into account the hours of work input, FTE employment rates can be a useful indicator in addition to the regular employment rate.

Comparing FTE employment rates puts especially Finnish older women in a positive light. Finnish men, on the other hand, perform poorly by international standards, especially when considering that part-time work is relatively uncommon among this group. This is a huge loss of potential, both for these individuals as well as for the country, and should be at the top of policy agendas in the coming years.